By Craig Duncan | ACICIS Intern at the Environment Institute

Photo: Australian Bush

By: Craig Duncan

Intricate networks of flora, fungi, and fauna thrive within the rich environment of Earth’s forests. One of Earth’s most complex and important ecosystems; forests contain over 60% of the planet’s biodiversity. [1]

These complex ecosystems harbour the majority of terrestrial life on Earth and play a vital role in the growing battle against climate change.

Forests as carbon sinks and carbon sources

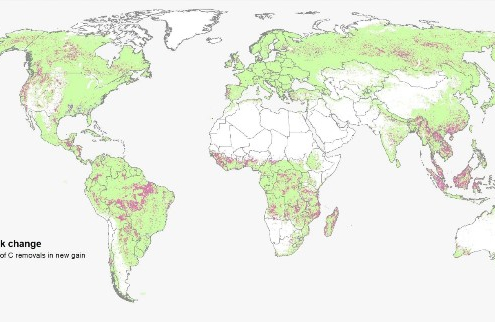

Source: Harris et al. 2021. [7]

Earth’s forests act as a ‘carbon sink’ sequestering carbon from the atmosphere into their internal structures. This process allows Earth’s forests to absorb 7.6 billion metric tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere each year. [2]

Yet, despite their massive biological potential, ability to reduce emissions, and providing everyone with the oxygen they require to breathe. Earth’s forests are currently being destroyed globally at a rate of 10 million hectares per year. [3]

If allowed to continue in our current trend, global potential canopy cover may shrink by around 223 million hectares by 2050. [4]

Currently, tropical deforestation and forest degradation is responsible for around 15% of carbon emissions per year. [5]

The destruction of these vibrant ecosystems decimates populations of animals reliant on these forests. The loss of habitat leaves many animals without homes whilst others lose their food sources, the majority lose their lives. Due to the interconnected nature of forest ecosystems, their destruction permeates through the environment, resulting in deforestation being one of the main causes of animal extinction. [8]

The history of Earth’s biodiversity has been a dramatic performance of coincidence and conflict. As it currently stands Earth has endured five mass extinction events in its lengthy history. The most recent ending the reign of the Dinosaurs in an explosive fashion.

65 million years on, we find ourselves at the precipice of a new extinction event. Earth’s sixth mass extinction – Humanity. [6]

Unlike these past extinction events, our current scenario has occurred rapidly and as the direct impact of humanity. The extinction rate of today is potentially 1,000 to 10,000 times the biological normal, with the total disappearance of around 1-10 animals per year. [8]

Australia | An Awful Example.

Australia is lucky enough to contain the 6th largest forest area on Earth, with 134 million hectares of primordial forests, 3.3% of the total global amount. [3]

Holly Leaf Banksia – Gelorup

Largest of the species | Registered with National Trust [11]By: Craig Duncan

Unfortunately, according to A WWF report, [9] Australia is the only developed nation to be declared a major deforestation front. Australia has been listed amongst the top 10 clearing countries of the world. [13] Compared to vastly more populous and developing countries such as Brazil and the Congo.

Since European arrival, Australia retains only 50% of its pristine bushland, the other half being permanently destroyed or degraded. [10]

The most common reason for deforestation within Australia is agriculture [13] with grazing land for cattle the majority. Infrastructure projects and mining are also responsible for a sizable amount of destruction.

Australia’s overwhelming deforestation rates have been catastrophic to the country’s uniquely adapted animal population.

A grim result of Australia’s abysmal environmental mismanagement has awarded Australia the world’s record for recent mammal extinctions. [12] Australia is recognised as one of seven countries that contribute more than half of global biodiversity loss. [13]

Many Australian icons are currently at risk due to a decline in native habitat.

Koalas and platypus [14] have been growing in risk of extinction due to the ‘black summer bushfires’ of 2019 and ongoing habitat destruction.

Similarly, the Western Ringtail Possum is a small arboreal marsupial endemic to the Southwest of Western Australia. In 2017 it was declared critically endangered [14]

Despite this, 70-hectares of prime Western Ringtail Possum habitat began being destroyed at the beginning of August 2022.

Western Ringtail Possum

By Craig Duncan

The Western Ringtail Possum | Endangered Resident of the Gelorup Corridor.

Bob Brown and Protestors – 31/07/2022

By Craig Duncan

The Gelorup corridor is a 70-hectare forest located in Southwest Western Australia. The corridor acts as a major habitat for numerous critically endangered animals, such as the Western Ringtail Possum. [15]

At the time of writing, this forest is a matter of contention for locals and environmentalists. The State and Federal Governments have approved the construction of the Bunbury Outer Ring Road which travels directly through the Gelorup corridor devastating pristine habitat.

Environmentalist and former Greens Party leader Dr. Bob Brown visited the corridor on July 31st to emphasise its significance. Dr. Brown described the planned road as “an absolute, utter disgrace for the whole country.”

The planned route for the B.O.R.R. would remove major habitat for the Western Ringtail Possum, with over 100 possums known to nest in the area. Community members and Environmentalists from the Friends of the Gelorup Corridor note, that if the deforestation goes ahead, all of these possums are likely to die. Pushing an already critically endangered animal closer to extinction.

Indonesia | A Similar Story

Indonesia contains 92 million hectares of forest within its landmass, 2.3% of the global total forest cover. Indonesia holds the 8th largest forest area on Earth. [3]

Indonesia, according to a WWF report, [9] is one of the countries with the most deforestation occurring. Indonesia also finds itself as one of the top 10 clearing countries in the world. [13]

Indonesia | Primary forests and tree cover loss

Source: Global Forest watch [2]

Two major contributors to Indonesia’s deforestation rate are the paper and palm oil industries. [15]

Indonesia’s main deforestation hotspots are the islands of Sumatra, Kalimantan and Sulawesi. [15] The island most impacted by deforestation is Sumatra, with less than 25% of its natural forest remaining, [16] the majority of which is significantly degraded.

As a result of Indonesia’s rapid deforestation, Indonesia has the second highest amount of endangered animals on Earth and is recognised as one of seven countries that contribute more than half of global biodiversity loss. [13]

Sumatra runs the highest risk of animal extinction, home to several critically endangered animals such as the Sumatran Orangutan, Sumatran Tiger, and Javan Rhino.

The Remaining Forests | A Hopeful Future

Sumatra is an extreme instance of total forest degradation, as a result, it has left some of the most vulnerable and high-risk animals on Earth in a very precarious position. With environments fragmented these animals have very restricted populations.

In 2016 Indonesia cleared close to one-million hectares of forest. [2] However, since 2016 Indonesian deforestation rates have been decreasing overall. In 2021, Indonesia cleared slightly over two-hundred-thousand hectares, significantly less than the approximated average. [2]

Indonesian Country Director for the Rainforest Alliance, Putra Agung states, that these fragmented populations are at high risk. However, due to growing government support and global awareness, there is still potential for change.

Putra Agung suggests deforestation is slowing in Indonesia due to a growing global pressure to preserve these forests, and government recognition and support. He also stated, however, the deforestation rates may be dropping as there is little left to remove.

The island of Sumatra holds one of Indonesia’s largest forests, the Gunung Leuser National Park. The forest contains critically endangered Sumatran Orangutans and Tigers.

Putra Agung talked about the potential impact continued deforestation in Sumatra could cause on populations of Orangutans. Living in the North of Sumatra, within protected national parks, which are surrounded by palm oil plantations.

Putra Agung said, “the Indonesian government, and many others have tried their best to keep this area clear from the expansion of (palm oil). And it is quite successful up to now.”

Indonesia is diverting towards the correct path, vehemently protecting its remaining forests. And with it, providing some of the most vulnerable animals on Earth a potential chance to avoid extinction.

Deforestation at Gelorup

By: Craig Duncan

References:

[1] Oljirra, A. (2019). The causes, consequences and remedies of deforestation in Ethiopia. Journal Of Degraded And Mining Lands Management, 6(3), 1747-1754. doi: 10.15243/jdmlm.2019.063.1747 [2] Global Forest Watch. (2022). Retrieved 7 August 2022, from https://www.wri.org/initiatives/global-forest-watch [3] The State of the World’s Forests 2020. (2022). Retrieved 7 August 2022, from https://www.fao.org/state-of-forests/en/ [4] Ding, J., Travers, S., & Eldridge, D. (2022). Microbial communities are associated with indicators of soilsurface condition across a continental gradient. Geoderma, 405, 115439. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115439 [5] – Venter, O., & Koh, L. (2011). Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+):game changer or just another quick fix?. Annals Of The New York Academy Of Sciences, 1249(1), 137-150. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06306.x [6] Cowie, R., Bouchet, P., & Fontaine, B. (2022). The Sixth Mass Extinction: fact, fiction or speculation?. Biological Reviews, 97(2), 640-663. doi: 10.1111/brv.12816 [7] Harris, N., Gibbs, D., Baccini, A., Birdsey, R., de Bruin, S., & Farina, M. et al. (2021). Global maps of twenty-first century forest carbon fluxes. Nature Climate Change, 11(3), 234-240. doi: 10.1038/s41558-020-00976-6 [8] The impact of deforestation. (2022). Retrieved 7 August 2022, from https://rainforests.mongabay.com/09-consequences-of-deforestation.html [9] Pacheco, P., Mo, K., Dudley, N., Shapiro, A., Aguilar-Amuchastegui, N., Ling, P.Y., Anderson, C. and Marx, A. 2021. Deforestation fronts: Drivers and responses in a changing world. WWF, Gland, Switzerland. [10] Homepage | The Wilderness Society. (2022). Retrieved 7 August 2022, from https://www.wilderness.org/ [11] National Trust – Holly Leaf Banksia (Banksia Ilicifolia). (2022). Retrieved 7 August 2022, from https://trusttrees.org.au/tree/WA/Gelorup/187_Yalinda_Dr [12] Ashby, Jack. “12 Extinction”. Platypus Matters: The Extraordinary Story of Australian Mammals, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022, PP.273-290. doi: 10.7208 [13] Heagney, E., Falster, D., & Kovač, M. (2021). Land clearing in south-eastern Australia: Drivers, policy effects and implications for the future. Land Use Policy, 102, 105243. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105243 [14] The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. (2022). Retrieved 7 August 2022, from https://www.iucnredlist.org/– Western Ringtail Possum – https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/18492/21963100

– Koala – https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/16892/166496779

-Platypus – https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/40488/21964009 [15] (2022). Retrieved 7 August 2022, from https://wwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/riau_co2_report__wwf_id_27feb08_en_lr_.pdf [16] Sumatra. (2022). Retrieved 7 August 2022, from https://www.eyesontheforest.or.id/backgrounders/sumatra